The Ancient and Modern Practice of Mentoring

Education by way of mentoring is an ancient practice. The term “mentor” derives from a character who served as the advisor to Telemachus, the son of Ulysses in Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey, written in the 8th century BCE. When Ulysses set out for the Trojan War, he entrusted his son’s care and education to his old friend, Mentor, who advised and guided Telemachus during his father’s absence.

Today, the term “mentorship” is typically used to describe a one-on-one relationship in which one party uses their experience and knowledge to guide the professional or personal development of the other. In the professional setting, the concept of mentoring has expanded to encompass multiple scenarios, including group mentoring and “reverse mentoring,” in which typically younger mentors guide their older peers in understanding modern developments, often in technology.

Technology has had a large impact on expanding mentoring, enabling mentors and mentees to connect virtually regardless of location—this has accelerated significantly since the pandemic often made face-to-face meetings impractical.

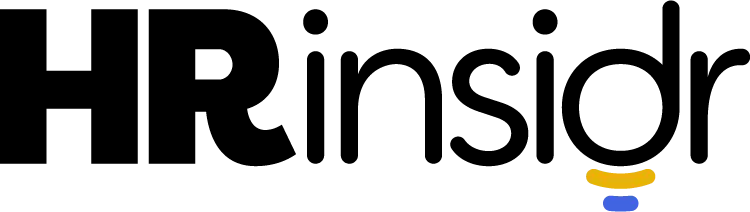

In a survey of 338 HR professionals across industries conducted by the HR Research Institute, the research arm of HR.com, almost two-thirds (64%) of respondents said their organization has a mentoring program, compared to one-third of those surveyed in 2017. Large organizations are more likely to have such a program (69%) compared to small (51%) and mid-sized (41%) companies.

HR departments are the heart and soul of mentoring programs, often responsible for building and maintaining programs that foster the professional development of employees at every level of their company. Whether such programs succeed or fail, the buck stops at HR. In fact, the advancement of HR professionals themselves may depend on how effective they are at growing the careers of a company’s employees.

Not a “Nice-to-Have”

For an organization to be successful, it must provide its employees with tools and training to advance their knowledge and careers. According to a workforce survey conducted by The Conference Board, a think tank that focuses on business issues, 58% of employees said they are likely to leave their company if they do not receive professional development, continuing education, or career training to develop new skills and drive their career advancement. Research by the Association of Talent Development, a professional organization of talent development professionals, found that organizations with mentoring programs see 57% higher employee engagement and retention.

Organizations with mentoring programs see 57% higher employee engagement and retention.

However, 36% of the respondents to the HR Research Institute said their organizations have no mentoring program at all.

Tried and True Mentoring Practices

The fact that today’s professional mentoring programs have been tested by trail-and-error for many years has led to common practices that are reliably successful, leading to the career development and advancement of many employees.

However, it’s still not uncommon for mentoring programs to fail or fizzle out, the victims of neglect, disinterest, poor organization, or lack of leadership support. In fact, according to a 2024 article in the Harvard Business Review, although 98% of Fortune 500 companies have mentoring programs, only 37% of employees say they benefit from them.

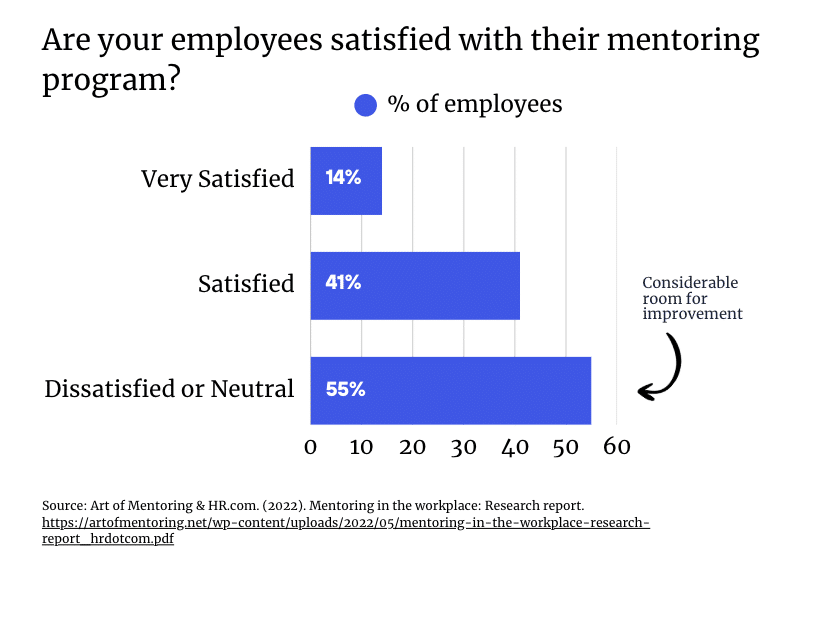

In response to the HR Institute survey, only 14% of respondents said they are very satisfied with their organization’s mentoring programs, 41% said they are satisfied, and 55% said they are dissatisfied, very dissatisfied, or neutral—leaving considerable room for improvement. The primary reasons given for dissatisfaction are lack of program structure, program inconsistencies, inadequate evaluation of programs, and low participation rates for both mentors and mentees.

Many of the factors that result in unsuccessful programs are easily remedied, however. HR departments that run strong mentorship programs often take the same actions:

1. Obtain strong leadership buy-in.

According to the United States Office of Personnel Management (OPM), which serves as the chief HR agency for the federal government, “A formal mentoring program will succeed only if senior leadership supports the program and makes it part of the learning culture. It is best to identify a champion (preferably a senior leader) of the program who will play a major role in marketing the program and recruiting mentors.”

The OPM also advises senior leaders to actively participate as mentors in the programs themselves, modeling its use to their employees. HR heads should make their organizations’ senior leaders aware of the programs’ success stories and ask them to personally call attention to examples in which mentors have helped their mentees advance in the company hierarchy or expand into different roles. If senior leadership is aware of and helps celebrate these success stories, it will be easier for HR to advocate for more resources for mentorship.

2. Assign and support a dedicated program manager.

The OPM says that the most successful mentoring programs include a full-time employee dedicated to managing and administering the program. But that’s rarely the case in most organizations. Only 7% of respondents to the HR Institute’s survey said that overseeing their organizations’ mentorship program is a full-time position.

Too often, employees who agree to be the managers of their organizations’ mentoring programs rarely have enough time in their schedules to adequately run them. Asked how much time their mentorship program manager devotes to their mentoring programs, 27% percent of respondents to the HR Institute survey said 1-2 hours a week, 14% said 3-4 hours a week, and 10% said 5-9 hours a week. An eye-opening 24% said they do not have a program manager at all.

When an organization’s leadership leaves program oversight to already-overworked employees, those programs often fizzle out from neglect. HR departments that successfully make business cases to their organizations’ leaders about the bottom-line value of well-run mentorship programs are more likely able to get program managers the time and resources they need to be effective.

3. Make good matches.

When asked to identify the top factors that are key to the success of mentoring programs, respondents to the HR Institute’s survey most often cited the willingness of mentors and mentees to spend time on their relationship (65%). Fifty-six percent cited the quality of mentor-mentee matching. No mentoring relationship will succeed if the mentor and mentee are poorly paired.

Being able to bring the right two people together in a mentoring relationship is both an art and a science. Mentoring Trends Media, which provides platforms and resources to bolster successful mentoring programs, states that “a thoughtful selection process that acknowledges individual capabilities and interests can drive the entire mentoring program toward success.” Key to doing this is identifying capable mentors and considering their experience, expertise, willingness to help others, and whether those factors can support what a specific mentee wants from the relationship.

To that end, mentees must be transparent about what their needs are if they want to progress professionally. Can a specific mentor successfully address those needs? And if a pair appears well-matched on paper, do they have the personal chemistry required to build the foundation of a successful pairing?

4. Provide adequate training and onboarding.

Only 45% of the respondents to the HR Institute survey said their organization provides training for mentees, and 54% said their organization trains mentors. That leaves plenty of program participants who do not receive formal instruction about their respective roles and responsibilities. When HR builds a mentoring program, they cannot just assume that the responsibilities of each partner in the relationship will be self-evident.

Onboarding, orientation, and training are the most common ways mentors and mentees are educated about their programs. They are given roadmaps on which to plot their success and checkpoints to gauge their progress. This puts them on the same page regarding expectations and mutual goals.

5. Evaluate and enhance your program. Frequently.

Mentoring Trends Media suggest in their mentorship guidelines that organizations “Encourage mentors and mentees to provide regular feedback to each other. This not only helps in personal development, but also allows the program to adapt and improve. Be open to making adjustments based on feedback to ensure the program remains relevant and beneficial for all participants.”

Mentoring pairs should also provide feedback to program administrators. Formal evaluations are essential to a program’s long-term success. HR should regularly survey program participants about what is and isn’t working for them. Ask them to identify any changes they would suggest, and involve them in modifying the program to better address the root causes of any issues. To maintain enthusiasm about the program, HR should also ask participants to report and share success stories with their departments and the entire organization.

Planning Is Everything

The bottom line is that HR cannot take for granted that mentoring program participants will automatically know what they need to do to get what they want out of it. The most effective mentoring takes place within a well-defined, formal program that outlines expectations and provides a framework for gauging progress. Building that foundation at the start goes a long way toward putting employees on the path to career success.