When Tragedy Strikes: How HR Can Help Organizations Prepare for the Worst

On June 28, 2018, a man who was upset with an article published in The Capital Gazette, a daily regional newspaper headquartered in Annapolis, MD, entered the publication’s offices. He barricaded two of the building’s exits and made his way to the room where reporters and editors were working to meet their daily deadlines. With a shotgun in hand and various weapons weighing down his backpack, he opened fire on the newspapers’ employees, killing five of them and injuring two others.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack, Josh McKerrow, a Gazette photographer who had been out of the office on assignment, rushed back to work when he learned of the shooting. McKerrow arrived just as the police were taking the shooter into custody, and he immediately went into reporter mode, taking photographs and asking questions.

Taking the information he had gathered out of the Gazette building, McKerrow spotted two other reporters who also had not been in the office at the time of the shooting. They joined forces and, sitting on top of plastic crates on the back of one reporter’s pickup, they propped up a laptop and began putting together the next day’s Gazette. One determined reporter tweeted, “We are putting out a damn paper tomorrow.” And they did, publishing a survivor’s report on the tragic deaths of their colleagues.

A Too-Common Occurrence

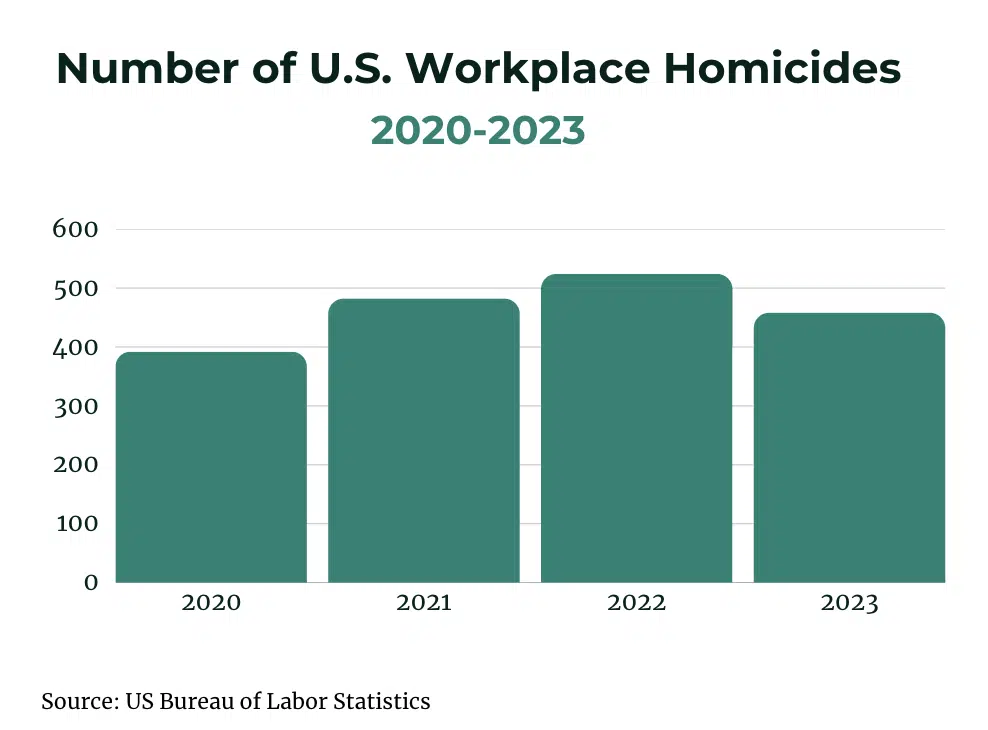

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), although it has decreased dramatically since peaking in 1994 at 1,080, the number of homicides resulting from workplace violence has begun a slow climb in recent years, from 392 in 2020 to 458 in 2023 (the last year for which statistics are available from the BLS). Of course, most episodes of workplace violence do not result in death; from 2021-2022, there were 57,610 nonfatal cases of workplace violence.

Since peaking in 1994 at 1,080, the number of homicides resulting from workplace violence has begun a slow climb in recent years.

The violence at the Capital Gazette, like many other workplace tragedies, had a tremendous but disparate impact on the staff who survived the incident. Some would return to work (in the case of McKerrow, on the same day), others took leaves of absence to process the event, some chose to leave their jobs, and still others would build on their experiences to advocate for stronger protections for journalists. Despite the many playbooks for handling tragedies in the workplace that have been written before and after the shooting at the Gazette, each incident and the employees it impacts are unique.

A mass shooting, of course, is among the extreme examples of high-impact workplace disruptions. Many other tragedies—such as a natural disaster, a workplace accident, the sudden illness of a much-loved employee, or an automobile accident that takes the life of a colleague—are far more common and hit workplaces every day.

While no two tragedies are alike, and no playbook exists that covers them all, HR professionals can adopt some best practices to help them be better prepared to handle the fallout when the unexpected happens in the workplace and its impact on staff is widespread.

1. Acknowledge what happened.

The best way for a company to acknowledge a tragedy that touches the workplace will ultimately depend on the nature of the incident, but there are some general guidelines for how to first respond to any disruptive event.

In the immediate aftermath of a tragic event, do not delay acknowledging it. Staying silent can give the impression that your leadership is indifferent to their employees’ welfare—or even worse—is hiding something. Your message doesn’t need to be polished. Simply recognizing that the event took place and affected your employees is enough in the first 24 hours.

2. Be empathetic.

When a sudden tragedy strikes, employees often just want their feelings validated. Advise your managers to acknowledge the pain their workers may be feeling and the importance of validating their right to feel that pain. Encourage them to demonstrate empathy by communicating that they don’t expect their employees to immediately resume their work right where they left it before the tragedy occurred. Just knowing that you will give them some grace time to process what has happened can take a load off workers’ minds and help them start to get their bearings.

3. Prioritize/redistribute work.

If a tragedy is large enough to impact a wide swath of employees, ask leadership to identify as soon as possible which tasks are essential to keep the business running, and which can be put on temporary hold while employees tend to their own well-being. If possible, assign crucial tasks to workers who may not have been as affected by the tragedy. Adjust deadlines for tasks that are not urgent for employees who may need some time to heal before returning to their regular schedules.

If possible, leadership should give impacted employees a few days off or offer a more flexible schedule, and adjust meeting times and deadlines accordingly. If remote work is an option, offer that to help employees work where they feel most the comfortable for the time being.

4. Listen.

Reinforce to your managers that when they lead with empathy, their employees will be more likely to respond with honesty. Encourage them to proactively reach out to impacted employees rather than waiting for their employees to tell them what they need. When a tragedy is particularly overwhelming, employees may not know what their needs are right away. Managers should ask their workers how they are and what might help them, and try to provide that, if possible. If not, let them know where other available resources can be found.

And don’t forget your remote workers. Managers often forget the employees they can’t see, especially if only a minority of employees are working from home. Urge management to contact those employees with a quick check-in call or message. Most remote employees already feel disconnected from the workplace to some extent. Knowing that they have their managers’ support can mean a lot to them.

When employees gather for in-person or remote meetings in the aftermath of a tragedy, advise managers to acknowledge what has happened and open the floor to any shared thoughts or questions. Simply asking them how they are feeling demonstrates to employees that you are aware of how the incident may be affecting them, and that you care about their well-being.

If an incident is especially difficult to recover from, think about ways of helping employees process it as a group. Suggest a candlelight vigil, an opportunity to share personal memories together, or a volunteer activity. The company may choose to make a donation in the name of the person at the center of the tragedy (e.g., a monetary donation to a disease-specific nonprofit, or college tuition money for the child of an employee who passed).

5. Share resources.

Employees recovering from an unexpected tragedy often have mental health needs that necessitate the services of a professional. Remind managers that they don’t bear the personal responsibility of meeting their employees’ emotional needs. Many organizations offer mental health benefits or access to an employee assistance program for those reasons. However, employees in the midst of a crisis may need to be reminded that those resources are available to them. Be proactive in telling employees about their mental health benefits and giving them information about how to access them.

Sometimes specific employee resource groups (ERGs) may be able to match employees with the services they need. For example, ERGs that revolve around bereavement, cancer support, or volunteering may be able to provide information about specific resources.

6. Make a plan.

While no crisis management plan can cover the fallout from every possible tragic incident, having one can help when a company’s leadership is confronted with an event that significantly disrupts their workplace. A robust plan builds on lessons learned by other employers who have faced similar tragedies, and it can provide structure for preparing for the unexpected.

Good crisis management plan templates are easy to find online. Their most essential element is the creation of a basic framework for responding to an incident. When an organization has been impacted by a natural disaster, a violent act, or a workplace accident, it’s essential to develop clear protocols to respond quickly and calmly. A basic preparedness plan will:

- Establish protocols for disaster response.

- Make the organizational chain of command clear (and provide fallbacks if the incident causes disruptions to that chain).

- Provide information on how to access local emergency services.

- Create a communications plan with built-in redundancies if typical communication channels are cut off.

- Establish a method for tracking the safety and well-being of employees.

- Provide guidelines for offering employees physical and psychological support.

More than anything else, building an organizational culture that prioritizes understanding, empathy, and flexibility is the best way you can prepare your employees for the unexpected. When organizational leaders have already done the hard work of earning the trust and loyalty of their workers, employees will instinctively look toward them for direction when they are confronted with a trauma in the workplace.

—